By Keith Walsh

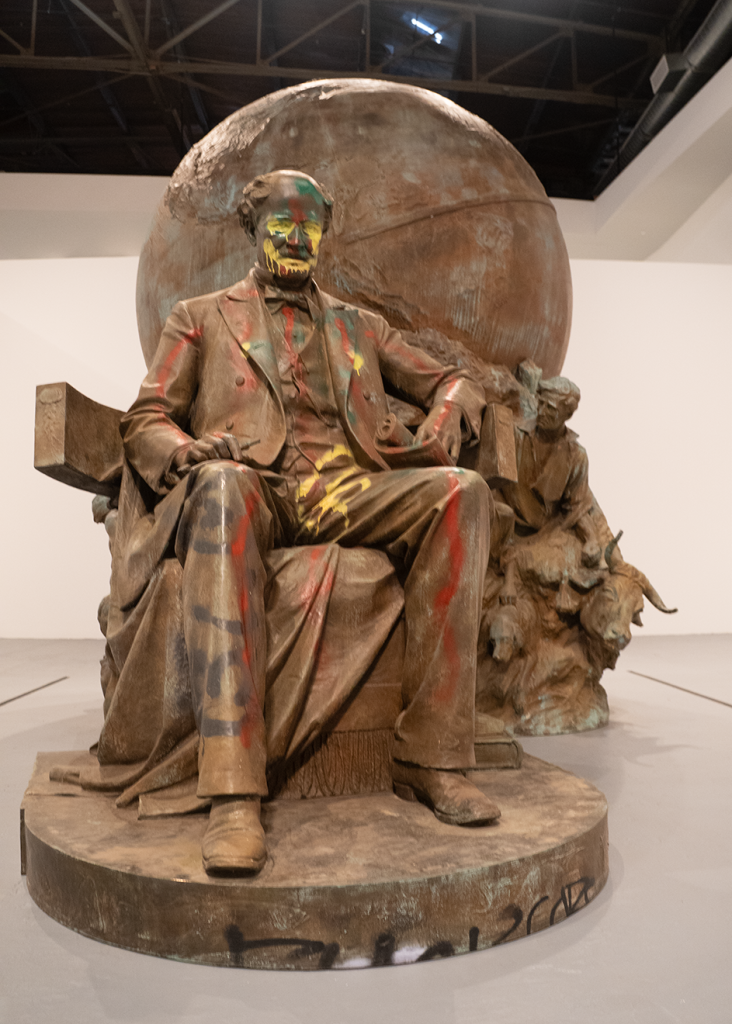

Like an unloved relative hauled away to be warehoused, in 2017 the city of Baltimore removed four statues in the secrecy of night: The Confederate Soldiers and Sailors, The Confederate Women Of America, The General Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson Double Equestrian, and a statue of chief justice Roger B. Taney. All four of these are now on display at the exhibition MONUMENTS, sponsored by MOCA at The Geffen and THE BRICK.

Like hydraulic systems, in societies the thing denied emerges in other ways, sometimes contemporaneously as in art forms, or in later times as narrative texts and investigations. The dialogue over these statues and others involves presidential orders and gubernatorial refusals to obey those orders, and are signals of a continual need to connect with our history in meaningful, constructive ways.

Enter the blues, a musical style that allows honest expression of feelings around being devalued in various ways. No investigation needed, it’s prima facie. The unique beauty and emphasis on emotions is proof of a higher ground.

It’s odd how beauty survives oppression. Privilege can be tolerated or possibly forgiven, depending on how sincerely it accepts the reality that dominance is only a provisional position, rather than an enduring condition. Percey Bysshe Shelly’s poem Ozymandias comes to mind. When understanding history, category errors abound, rationalizing the past. A category error is akin to evaluating a singer songwriter by the standards of canvas painting, failing to acknowledge that the two categories of artists are managed by variable, programmable standards of discussion and visibility. MONUMENTS demonstrates how the deferred dream of equality is still emerging and is contingent on understanding.

The conflict over who should control representation of a shared history brings to light anxieties over fears that the media are controlled by mischievous forces wishing to create disorder rather than promote understanding, and fantasies about control over complex circumstances with tendrils reaching backwards and forwards in history for centuries.

A 2024 National Monument Audit by Monument Lab reveals that four out of five Confederate monuments are still standing. From a video installation at MOCA sharing data from the Monument Lab: In these monuments, “10 of the top 50 people most represented in monuments were enslavers. There are more monuments to Robert E. Lee, the general of the losing Confederate Army, than to Ulysses S. Grant, the general of the winning U.S. army, and later a U.S. president…in the top 50 people depicted in monuments, there are more confederates than black Americans. What we are left with is a monument landscape that disproportionately lifts up the confederacy and lost cause.”

The MOCA exhibition presents art in various states that show the value of creatively recontextualizing the past rather than burying it, with graffiti covered detritus displayed alongside historical and contemporary photos and sculptures. Ten feet tall portraits of Klansmen photographed in 1990 by Andres Serrano were so distasteful that I didn’t dare photograph them. An array of recently discovered negatives printed into photos from Hugh Mangum, who passed away in Virgina in 1922 are stunning. Paintings by Walter Price celebrate emotions in contemporary color.

The Warden, a presentation featuring Miss Confederacy aka The Vindicatrix that was atop a dismantled Jefferson Davis monument with the words Deo Vindice (God Will Avenge) features electronics including a live video feed suggesting the liberty might be enhanced by surveillance. A relatively recent monument from 1948 celebrating Robert E. Lee’s victory and another from 1985 of pro slavery newspaper publisher Josephus Daniels demonstrate the resistance to change.

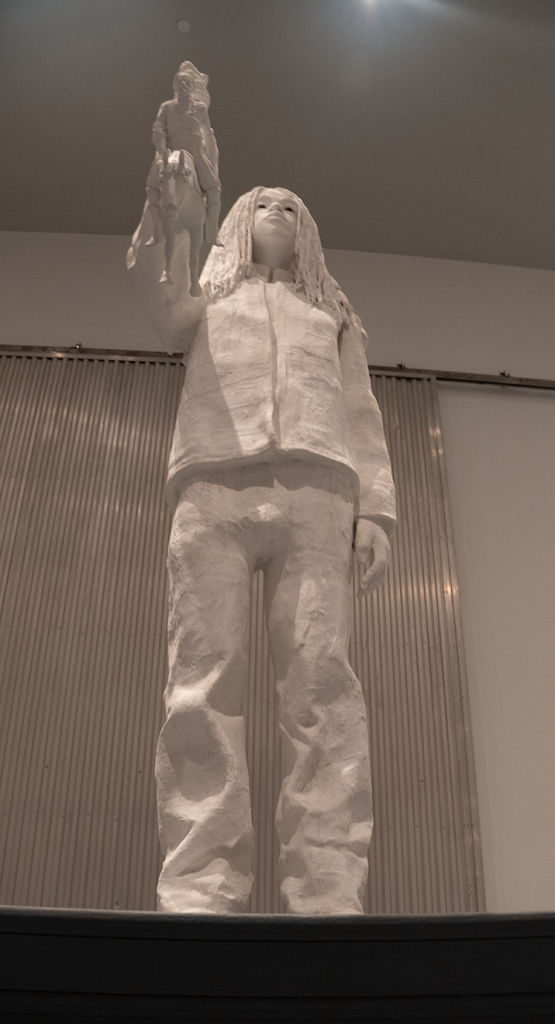

Josephus Daniels by János Farkus, 1985, and The Descendent, by Karon Davis, 2025

I wasn’t prepared for how emotionally impactful the exhibition is: it’s a blow to the soul when one’s imagination feels some of the heavy emotions that coincide with a history that overlooks the heart. There’s no denying the aesthetic beauty of all of it, and that feeds into the cognitive dissonance.

Photos by Keith Walsh

KfW 10_24_25

MOCA CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUM

Monument Lab

Percy Bysshe Shelley’ Ozymandias

finis